// The sixth power //

“I’d rather Goya robbed me of my sleep than some other arsehole.”

These are not my words. They are from Rodrigo García and his company La Carnicería Teatro. This sentence is also the title of one of García’s most brilliant works. The play deals with a fifty year-old man who has saved five thousand euros in the bank and wants to spend it on something worthwhile. His plan is to sneak into the Prado Museum at night with his children and bring along snacks and drinks to see Goya’s Black Paintings. The kids would rather go to Disney World. García says, “The oldest of my two kids says that, to understand the sadness of modern man, it would be better to spend a little time with Mickey Mouse in person – that is, the underpaid teenager roasting for twelve hours in a plush suit without breathing holes – than to gaze at Saturn Devouring His Son or Fight with Cudgels or anything painted by Goya, Velázquez, Zurbarán or El Bosco.”

García tells us about a worn-out world in which a lifetime of effort translates into a sum of money in a bank account. A world of inverted values depicted in the sadness of a young underpaid man suffering while concealed under a false illusion of prosperity. Something has failed in a society where the word “selfie” means so much more than the name “Goya.”

I don’t think I’m saying anything new here, but let me remind you of a few things. The world is disgusting. We all know it. It’s organized in such a way that the only thing left is the escapism of Mickey Mouse. Goya is too boring, he tells us nothing. And that applies to those of us who have a roof over our heads and a hot meal. For the vast majority of human beings, the world is even more disgusting. We have confused development with progress. The first is an economic issue, with a few champion fighters and a mass of people aspiring to win the regional title. The second refers to the overall progress of an entire society.

Not that I realized this while watching Rodrigo García’s play. The world was already disgusting long before I left the theatre. However, this artistic experience led me to reflect, and wonder what I could do to change the world and make it better. I am socially useless, the kind of person whose inaction actually inhibits progress. I don’t go to demonstrations, attend protest meetings, work with charitable causes, or raise any kind of flag. I am not an activist. I admire those who are, but their actions are only palliatives that do not solve the root problem. Someone always manages to defeat those who are united in protest. The real problem is unethical ambition – without awareness of others – and the resulting social model.

How can we reverse this model?

When I went to bed I was still socially useless, but in the middle of the night Goya appeared to me, and spoke to me about the monsters that create the sleep of reason. Then I realized: “A teacher! I have to be a teacher.” Education is the best form of activism I can think of. Helping shape free citizens is my idea of a social revolution. A world of beings prepared to think – it may not be the best of all worlds, but at least it’s a better world. This kind of social progress is shaped by critical, free beings who are able to make choices guided by moral deliberations. I’m not saying that looking at paintings by Goya – high culture – is the way to go. I’m talking about a communal feeling that is easier to experience when you have already learned about it.

Should education instill a canon of values and pre-established knowledge towards this end? Is there a recipe for social progress? Let us turn to etymology. The word “educate” stems from two Latin verbs, educare and educere. The first, which more closely resembles the verb in Spanish and English, as well as the dominant models of education, means “to form, to instruct.” This kind of education teaches individuals to conform to a social group and internalize its culture. But human beings should be able to transform their environment and aspire to social progress. This does not come about by simply assuming the values and knowledge inherited from the previous generation. This is where the value of the verb educere – meaning “to lead, to draw out” – becomes apparent. In this sense, education should help the individual translate their potential into action; it should promote self-determined learning, where the protagonist is an individual on a path of discovery, and does not merely assimilate what has been discovered by others.

The Greeks gave us the concept of maieutics, which comes from maieutiké techné, “the art of the midwife.” Socrates compared teachers to midwives, helping their disciples “give birth” to knowledge and find the truth for themselves. But no one is interested in this – it’s a drag, and requires effort from both sides. As seen in Erich Fromm’s famous book “The Fear of Freedom,” it’s not always easy to renounce letting others decide for you.

Since the Industrial Revolution, education has become a tool for training skilled workers and has evolved and adapted to new market requirements. It has been understood as educare instead of educere; education designed to transmit automatism instead of promote human enhancement. In short, it is a tool in the service of economic development rather than social progress.

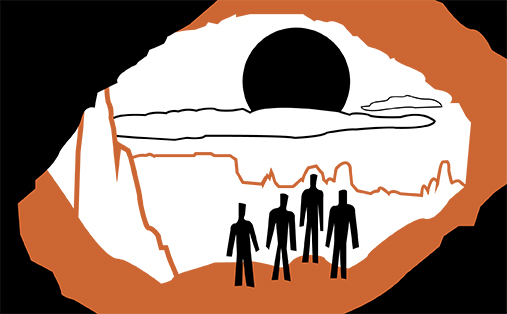

The education of each generation – both formal education and also in the sense of socialization – is always determined by the preceding generation. Progress is obstructed by the perpetuation of the current model, the model of those already in power. However, if students could be more autonomous, they could shape their own reality and inform themselves – in an etymological sense – based on their own interests. Plato explained this in the “Allegory of the Cave.” Try to stop seeing the reflections of objects on a wall, and start seeing the objects themselves. This would at least be a first step towards social progress, although “coming into the light” and reaching the truth sounds grandiose and utopian.

The sixth power

The concept of the separation of power that emerged during the French Enlightenment was one of the great advancements in social progress. Also in the eighteenth century, the UK gave us the idea of the media and the free press as a fourth power to watch over the other three. In the current international situation we know that they are merely tools of the so-called fifth power, which in reality is the first: economic systems.

Media channels have become monitoring instruments. The fourth power has failed in the task with which it was entrusted, to create a new way to regain the control that was taken from us while we slept the sleep of reason.

The real revolution is to “give birth” to critical, ethical, free, educated citizens, to establish a sixth power that can regulate the other five – to create a world on a human scale. Economic power is the final monster in the videogame – we must strip it of its title of “first power.” Selfishness is ignorance. An educated individual will understand this truth, will comprehend that it is better that we all eat, that no one freezes, that we have the power of choice. Not everyone will accept this, but many will try and stop those in power. We have to start somewhere. Human ambition will carry on until this becomes the standard, a faithful companion.

Creating a world in which each individual is the master of his or her own destiny is a difficult task because it entails a complete transformation of society. It is a two-way process, and a complex goal in a world that demands cheap, obedient, or simply disenchanted workers. We must establish that sixth power. Every citizen should be a teacher, or a midwife, working to change the social model so that history is no longer driven by economic relations, but rather by the principle of happiness and individual freedom of choice. Our generation has already gone awry, but we can still “give birth” to the generations to come.

In the end, Rodrigo García’s children agree to sneak into the Prado to see the works of Goya instead of going to Disney World. This is a simple revolution, within everyone’s reach: the intention to focus solely on the things that matter, the things that explain our world and ourselves. Become the sixth power – and as Francis Ford Coppola once said: “Be spectacular.”

Patricio de la Torre Becerra

Patricio de la Torre Becerra was born in Granada, Spain in 1979. He graduated with a degree in communications from the University of Seville and has a master’s in language and literature from the University of Granada. Over the past 15 years, he has enjoyed a meteoric journalism career in various media. He currently works as a journalist for Deutsche Welle, Germany’s international broadcaster.

Manuel Cabrera

Manuel Cabrera was born in Mexico City in 1986. He studied graphic design at the Universidad Iberoamericana. He currently works as a graphic designer and illustrator while he pursues a degree in architecture.

December 2014

© Santacruz International Communication