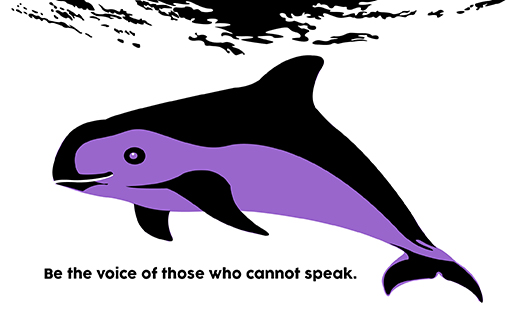

// Let’s Save the “Vaquita Marina” – the Desert Porpoise //

“If there were only a hundred of us left, would the desert porpoise help us?” This is a reflection of one of my fourth grade students in a talk about endangered species.

Learning about biodiversity and its interrelationships, the children thought it would be a good idea to help endangered species. They started by selling recyclable paper, cardboard, and cans – and collecting donations in school. This led to a contribution of $165 USD to the WWF (World Wildlife Fund) to adopt a crocodile, a dolphin and a red fox.

The vaquita (desert porpoise) in the Gulf of Mexico needed their help urgently. What could they do? They decided to ask adults for help. One of the parents agreed to help his daughter by letting us use his crowdfunding page to collect money to donate to Greenpeace. But the fourth grade students needed a bigger team to make this come true. To start with, they created a video to promote the campaign for donations. Represented by four students, the entire class participated. The goal was to collect $50,000 MXN ($3,500 USD) to donate to Greenpeace. The school group put all of its energy into the project. Some drew pictures, others made clay sculptures and designed the prizes. A great video was recorded and uploaded to the Mexican crowdfunding platform Fondeadora under the title “¡Salvando a la Vaquita Marina!” (Save the Vaquita!)

While we were working on the project, we learned that Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto was planning a trip to Baja California on April 16, 2015. My students and I wrote letters to him explaining our efforts and telling him how much we care about the desert porpoise. We asked him to share our concerns about the ecosystem.

After the video was uploaded to the Fondeadora website, the online version of the Mexican newspaper Milenio published a report on the day the President traveled to Baja California.

Five days later, the children had reached their funding goal! Their emotion and excitement was unbelievable!

Following a suggestion by of one of the parents, we asked a local radio station to promote our project. Eight of the students were invited to talk live on air. The preceding radio program was about SEMARNAT (Secretaría del Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales/Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources) and the following broadcast focused on Greenpeace.

I was interviewed by “La Entrevista Verde” (The Green Interview) on RED AM radio and our group was invited to appear on a television program called “Women and Ecology” on Green TV. The focus of this program is to raise awareness of the importance of caring and taking responsibility for our world’s biodiversity.

The following is some of the information they shared based on their very enthusiastic research in the classroom.

One of the two smallest cetaceans in the world, the vaquita, or desert porpoise, is less than 1.5 meters in length. It is endemic to Mexico’s Gulf of California, also known as the Sea of Cortez, near the estuary of the Colorado River. It is one of six species of porpoise. The word porpoise is based on Latin porcus ‘pig’ and piscus, ‘fish’. With dark rings surrounding the eyes, patches on the lips and a thin line from the mouth to the pectoral fins, vaquitas are among the cutest sea mammals. The dorsal surface is dark gray with pale gray sides and a white ventral surface with long, light gray markings. Desert porpoises eat ocean fish, including Gulf croaker, bronze-striped grunts and squid. They use echolocation to communicate and navigate Gulf waters. They are inconspicuous and illusive, avoid boats, and are considered to be very shy. Females reach maturity sometime between 3 and 6 years of age, and males appear to be similar. Females give birth perhaps once every two years, with most calves born in spring after a 10-11 month gestation period. The maximum known lifespan is 21 years. They are most often found close to shore in the gulf’s shallow waters.

Very few people have ever gotten a good look at a live desert porpoise. When seen, they are either alone or in small groups of two or three. Unfortunately, this mammal is on both the U.S. and Mexican endangered species lists as well as on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. The species is critically endangered primarily as a result of entanglement in fishing gear, especially gillnets used to catch shrimp and fish. The estimated mortality from gillnet fishing ranges from 39 to as many as 84 desert porpoises per year, which is clearly unsustainable. Desert porpoises are not the intended target of any fishery. As was also the case with the baiji in China, they are mostly the bycatch of local fishers trying to earn a living and feed their families. Sadly, the desert porpoise is a case of collateral damage. The species is also threatened by the decreasing flow of fresh water from the Colorado River into the Gulf of California. This is partly a result of the growing demand for drinking water in the western U.S. The water that flows to the Gulf carries high levels of agricultural runoff that can significantly alter the water’s chemistry. Illegal fishing for totoaba also contributes to the problem.

Despite new laws, specially designated reserves and fundraising efforts, the vaquita population continues to decline. Many organizations have pledged their help, including Earth Ocean, WWF World Wildlife Fund, INE Instituto Nacional de Ecología, Whale Trackers, Ocean Foundation, VeoVerde, Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, PROFEPA Procuraduría Federal de Protección al Ambiente, CEDO Intercultural Center for the Study of Deserts and Oceans, SEMARNAT Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales , the Mexican Navy (Armada de México) and Greenpeace.

According to Greenpeace, the estimated number of desert porpoises has declined to only 97 animals. This number has dropped from an estimated 567 vaquitas in 1997. The baiji, also known as the Yangtze River dolphin, was found only in the Yangtze River China. In 2007, it became the first cetacean species to be declared extinct in modern times as a direct result of human activities.

The government of Mexico has developed a plan to save the desert porpoise. Joined by U.S. Ambassador Anthony Wayne, Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto traveled to Baja California on April 16, 2015 to announce a bilateral commitment to save the desert porpoise and the entire ecosystem in support of biodiversity in Mexico.

The Mexican President banned fishing in the desert porpoise reserve area for two years and announced four components of the government’s strategy. The desert porpoise’s reserve area was nearly doubled from 5,600 km to 11,000 km. Fishermen’s compensation with alternative livelihood options will be offered. Mexican marines will be guarding the entire Baja California Peninsula and three Defender FC-33 ships were deployed in the area for this purpose. The Mexican Army will be working with these marines to enforce the removal of fishing nets and the use of sustainable nets. A critical part of the conservation is to monitor the desert porpoise over two years.

According to the Mexican President, Mexico represents one percent of the Earth’s surface and contains ten percent of the Earth’s diversity.

American ambassador Anthony Wayne said that U.S. President Barack Obama plans to stop illegal fishing of the endangered totoaba, a species of fish that commands very high prices in the Chinese black market. To complement Peña Nieto’s plan, efforts will be made to halt illegal trade of wild fauna.

One day later after the announcement, on April 17, 2015, two fishermen were caught illegally fishing for totoaba in the reserve area. According to newspaper reports, the fine for illegal fishing could be up to $3 million MXN ($200,000 USD) and 12 years behind bars.

What is currently needed is public support. Fishing is still the greatest threat to cetaceans worldwide and the fishing industry kill hundreds of thousands of marine mammals every year. We still have a chance to do something to save the Earth!

Empowered by teachers and parents, ten year-old children can accomplish wonderful things! It was truly amazing to see the energy and enthusiasm behind their project and how this transcended into each child’s family and community. Working together toward a common goal made every single aspect of this project important.

Eckhart Tolle’s quote in his book “A New Earth” applies perfectly to ecological conservation and life in general: “The Universe is an indivisible whole in which all things are interconnected, in which nothing exists in isolation.”

Adriana Santacruz Moctezuma

Adriana Santacruz Moctezuma graduated from Universidad del Valle de México with a master’s degree in educational sciences and has worked as an English teacher in her native Mexico for 30 years. Teaching in different schools, she has worked with students ranging from preschoolers to adults. She has supported the change in teaching methodologies from traditional teaching to constructivism and has witnessed technological evolution. She believes that teachers should serve as role models for their students and inspire them to make life decisions. Her approach to clarifying concepts uses question-based planning to promote reflection and encourage students to take action.

Manuel Cabrera

Manuel Cabrera was born in Mexico City in 1986. He studied graphic design at the Universidad Iberoamericana. He currently works as a graphic designer and illustrator while he pursues a degree in architecture.

May 2015

© Santacruz International Communication