// Dance matters! //

As a young schoolgirl, having just joined my local ballet school and immersing myself in the fairytale land of princesses, swans and spirits, it was fascinating for me to learn about the forager’s dance in biology. The very idea that bees could have a set choreography that they follow inherently in getting to and from their hives intrigued me and conjured up childish images of a corps de ballet of female worker bees perfecting their pirouettes, fouettés and grands jetés. However, it made me aware of just how important movement and dance is for the individual and society as a whole.

Dance is a form of communication and without the necessity of the spoken word it can cross boundaries delivering powerful visual messages. Tribal dances in Africa were performed mostly to express joy, to celebrate the coming of the new season, the birth of a child, marriages and even to commemorate the life of one departed. These dances taught social patterns and values to help people work and mature but also to express the life of their communities.The Native American rain dance was a ritual intended to invoke rainfall and would often be performed to new settlers in return for trade items and the Aborigines of Australia would also exchange songs and dances at large ceremonial gatherings at a time when goods were being traded. There was a purposeful reason to perform which required participation by all.

In most countries around the world, the folk dance evolved around occasions of celebration, because there was a recurring tendency to get together which invariably lead to some form of group dancing. Community dances were chosen for their simplicity of form allowing immediate application to the novice who found instant success and rich rewards. The dances were often performed in equal numbers of males and females and in the form of a square, promoting team work and a certain amount of social give and take. These dances would have been handed down through the generations and would not have had a choreographer responsible for setting the steps.

During the Renaissance period, that great social and intellectual movement which freed European thought from the restraints of medieval Christian philosophy, a distinction between court and country or folk dances was beginning to emerge and dance masters were duly employed to train dancers to be able to perform their work professionally, as entertainment for the nobility. These dances would be carefully notated for future revivals. Through the courts of kings began the development of dance as a visual art establishing an important platform for artists, composers, designers and choreographers. The court gathered as many artists as they could afford, understanding that the impact of such a combination of several arts was far more powerful and immediate. The new form became a leader of the arts and because of its flexibility was easily adaptable to particular themes, important at the time. The Court ballet originated in Italy but soon spread to most other European monarchies because of its popularity and splendor.

The importance of subject matter was paramount for the choreographer and in the days of the Imperial Theatre in Russia during the late nineteenth century a librettist would have been employed to work alongside the composer to prepare the foundation for the work. These were large scale, mammoth productions tailor-made for an audience bent on spectacle and grandeur and at times the choreographer’s own tastes had to be compromised to satisfy those of his spectators. At the beginning of the twentieth century, during the Russian revolution, the impresario Serge Diaghilev arrived in Paris with his Ballets Russes and took Europe by storm. He sought out the composers like Stravinsky, Debussy, Poulenc and Prokofiev to write the music, designers like Benois, Bakst and Goncharova for sets and costumes to support his cache of young dynamic choreographers, Fokine, Massine, Balanchine and Nijinsky to name but a few. Although many of the creations were knowingly good clean storytelling, Diaghilev was not opposed to controversy and through Vaslav Nijinsky, he caused uproar with audiences in Paris with Le Sacre du Printemps which introduced a new and avant-garde style of dancing accompanied by a complicated score by Stravinsky.

Out of this movement, fresh influences were appearing, removing the story from the dance altogether, demanding much more emotion and passion. It was no longer acceptable to produce sweet and obedient whimsical forms but to emanate profound new ways of dealing with character and drama, effectively loosening the rigid formulas. The ravages of the First World War, the Depression Era of the twenties and the rise of the Third Reich in the thirties brought about a development of compositional theory forcing dancers and choreographers to question and re-examine their craft in the light of the violence, social unrest and disruption. In Germany prominent figures like Mary Wigman and Rudolf von Laban introduced a new movement, “Ausdruckstanz” (free dance), part of the Expressionist Movement in art, which paralleled modern dance being introduced at the same time in the United States by Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn. For example,The Green Table choreographed by Kurt Jooss in 1932 for the Folkwang company he had founded in Essen was described as a dance of death in eight scenes depicting fruitless discussions of diplomats around a table while the horrors of war and its effect on ordinary people raged on. It was a strong anti-war statement choreographed one year before Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany. Jooss preferred themes attacking political and moral issues of the time and when refusing to dismiss the Jewish dancers in his company in 1933, he fled the country with his troupe of dancers and settled in the United Kingdom where he was able to continue with his craft freely and openly. The English choreographer Antony Tudor influenced by Jooss, was producing works which examined the psychology and emotional stress in human lives as well as grief and bereavement. His Dark Elegies from 1937 reflected the tensions and frustrations of the thirties. Pioneers of American modern dance, Doris Humphrey and Martha Graham were interpreters of aesthetics and keen observers of physical and emotional behaviour and were instrumental in developing modern dance as we know it today.

Thankfully the process continues and there are many gifted choreographers currently creating great thought-provoking works making use of state of the art technology available to them for their productions. Often the choreographic process includes discovering and defining the theme and intention and in the working, in the moving, something happens, something connects and something becomes important. José Limón, the Mexican-American dancer, choreographer and teacher who studied with Doris Humphrey, wrote in his contribution to Selma Jeanne Cohen’s publication, The Modern Dance: Seven Statements of Belief, “The artist’s function is perpetually to be the voice and conscience of his time”. Every artist-choreographer knowingly or unwittingly takes a stand and makes a statement beyond the content of the dance itself.

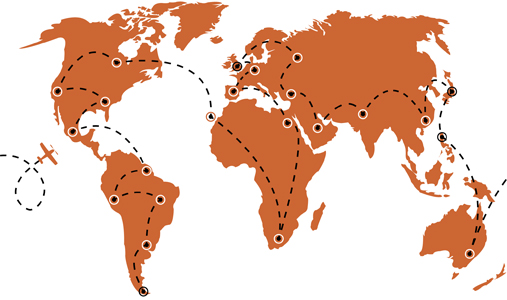

Under the influence of globalisation, many dance genres have become internationally known such as the tango, salsa and hip hop for example, even though they have been far removed from their birthplace and hybrid dance forms have also been accelerated into Western culture like the ever popular Bollywood film industry which juxtaposes traditional Indian folk dance with Broadway style musicals. Migration has played its part in globalisation as well. Once upon a time it was impossible to see a Russian ballet company perform anywhere other than in their own state but now choreographers themselves have become international stars with their works being reproduced for dance companies all over the world. It has been said that this has diluted any national and individual style of a company but it is something which is demanded and expected, not just by the company’s board of directors but also by the theatre-goers. It is also invaluable for the survival of the art both for the dancer and the spectator. Dance may not stop wars or change political viewpoints but as an art form it creates a unique statement that will involve its audience in some meaningful way. Dance matters!

Sources

Ballet for all – Peter Brinson and Clement Crisp

The Art of Making Dances – Doris Humphrey

Alison Kent

Alison Kent studied classical ballet and contemporary dance at the Rambert School of Ballet in London and danced professionally for fifteen years. She is now a freelance dance writer and critic for Dance Europe and lives in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany

Manuel Cabrera

Manuel Cabrera was born in Mexico City in 1986. He studied graphic design at the Universidad Iberoamericana. He currently works as a graphic designer and illustrator while he pursues a degree in architecture.

December 2013

© Santacruz International Communication