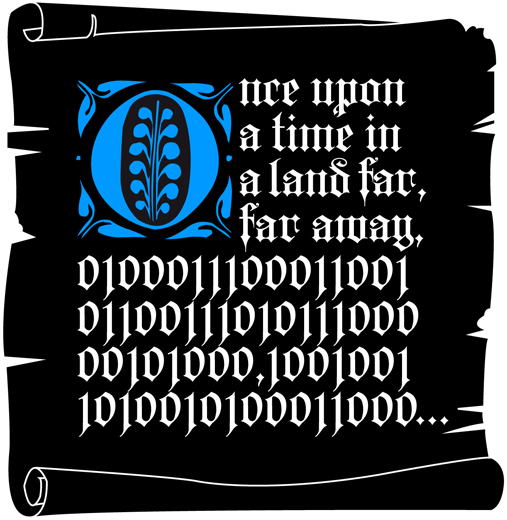

// Every Desk – A Vietnam //

“It can be said in all seriousness that journalism (the be-all and end-all of everything, as Aesop would have said) has created for man a completely new life, full of progress, profit and preoccupation. It is humanity’s mouthpiece, which comes every morning to tell us when we wake up what people have been doing the day before, proclaiming sometimes great truths, sometimes great lies, but always recounting mankind’s every step and recording the acts of the body politic… “

The French aristocrat Amandine Aurore Lucile Dupin, better known as George Sand, wrote the opening paragraph of this text on the island of Majorca between 1838 and 1839. With the French Revolution still fresh in the minds of the elegant intelligentsia of the time, Dupin (or Sand) clearly described the value of journalism (the ability to skillfully tell stories that are more or less relevant to all of society) in modern times.

As we approach the 200th anniversary of Dupin’s words, some seem determined to forget journalism – like they forgot modernity, a historical period when reason was used to describe reality and was an important aspect in the search for truth. When postmodernism came along, the concept of truth seemed to fly into a thousand pieces, as did the importance of the search for truth. With postmodernism, everything became relative and multifaceted. And so did the truth, the ultimate goal of honest journalism.

Dozens of media outlets closed and thousands of journalists around the world lost their jobs. There was a seemingly unstoppable trend towards poorer working conditions for those information professionals who still had a job. It all seemed to corroborate those ominous voices that are so popular in postmodern relativism. They try to redeem the noble profession of (trying to) explain what is happening in our everyday surroundings, by asking questions and answering them with more questions.

The best of all possible worlds

A decade ago, the trend towards poorer working conditions for journalists in European countries like Spain had already begun. Europe had settled into an economic, political and identity crisis with unpredictable consequences, but it still seemed to exist in the best of all possible worlds. National economies grew, jobs were created, banks extended credit and citizens consumed.

The virtuous circle of the capitalist system was functioning perfectly. But both in the media and at schools of journalism, the word was spreading: There was no future in the profession of telling stories. As I write these lines, ten years later, I ask myself: Did the big media conglomerates pave the way for what was to come?

Be that as it may, the future is here. Newsrooms for daily papers, which used to be indispensable references for deciphering global reality, are now deserted (or in the process of being abandoned). Information companies have been taken over by groups whose interests have little or nothing to do with good journalism. Cut and paste has replaced serious, honest investigation. Professional journalists are afraid of losing their jobs and avoid uncomfortable questions about the political and economic powers hanging over them. These journalists betray the very essence of their profession: to ask questions that lead to more questions, to find answers that convey some amount of truth to the reader, viewer or listener.

So, is journalism doomed? If it is indeed dead, has the journalistic profession really lost all reason for being? After the systemic crisis of capitalism began, we learned that European countries like Spain are far from living in the best of all possible worlds. We now have another exclusive story: good journalism will survive for another ten years, in spite of all the financial difficulties it faces and will continue to face. Paradoxically, good journalism’s poor but robust health has a lot to do with the destructive and pervasive economic crisis.

Poor journalist, annoying journalist

“A meager bank account and some anger in the gut stimulates good journalism,” says Enric González, ex-journalist for the Spanish newspaper El País and currently on the payroll at El Mundo. He lost his job in one of the last waves of layoffs by the current management of what was once a great newspaper (the first publication mentioned).

As González put so nicely, in general, the more money a journalist has in the bank, the less uncomfortable their questions and the less incisive their stories. Ten years ago, Spanish investigative journalism television programs were doing very badly, while “trashy”, insultingly low-quality shows garnered large audiences. When information professionals were asked why this was the case, their answer was always the same: “It’s what people want.”

In Spain, the times of plenty, the eternal flow of credit and the virtuous circle of capitalism are history. People’s taste also seems to have changed, at least in part: indispensable, recommendable and incisive investigative television programs like “Salvados”, directed by Jordi Évole, earned more than 15 percent of the ratings. This would have been unthinkable ten years ago when Europe “lived” in the best of all possible worlds. These general interest programs address difficult issues and have the political and economic power to recover a slot that was lost when everything seemed to be better than it is now.

In his book “Memorias líquidas” (Liquid Memories), Enric González confesses that Catalan journalist Josep María Huertas Clavería was instrumental to his career: “Each writing desk, according the ‘Huertas’ doctrine’, should be a trench of resistance against companies and other powerful players. I am a follower of the ‘Huertas doctrine’, which believes that the legitimacy of a newspaper is in its editorial, not in the interests of its owners,” writes the former El País journalist. Jordi Évole, director of Salvados, has also declared himself to be a faithful follower of the “Huertas doctrine”.

So, in spite of the economic crisis (or precisely because of it), no one is further from the truth than those who proclaim the end of journalism to the four winds. This prediction is as much in error as the “end of history” foreseen after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War.

Whatever they say, there is no substitute for this profession; it is of irreplaceable value. As Enric Gonzalez passionately writes: “We must not forget: each desk, a Vietnam. We must resist; we must always try. The journalist is paid to be a journalist. Everything else is for the bosses.”

Andreu Jerez

Andreu Jerez, born 1982 in Murcia, Spain. After studying journalism at the Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona and working in different media in the Catalan capital, he decided to go to Berlin, sensing a looming crisis for the economies of southern Europe. He currently works in the German capital for media channels including the international German broadcaster Deutsche Welle, the Spanish daily ABC, the Catalan weekly Directa and the online portal esglobal.org. Jerez is also a member of the journalist group Contrast, and posts articles and other genres on his personal blog cielobajoberlin.blogspot.de.

Manuel Cabrera

Manuel Cabrera was born in Mexico City in 1986. He studied graphic design at the Universidad Iberoamericana. He currently works as a graphic designer and illustrator while he pursues a degree in architecture.

February 2014

© Santacruz International Communication